Say what you like about his plays, but Anders Lustgarten knows how to deliver a line. “Most people who go to the theatre are sort of beyond salvation,” he declared a few years ago. More recently, he informed the Huffington Post that “80% of theatre was bourgeois wank”. His thoughts on David Hare, whose work he experienced as a teenager, verge on the unprintable.

The man who greets me in a Brighton cafe, with a boxer’s squat frame and blokeish, bone-crunching handshake, does indeed look as if he’s spoiling for a fight. But Lustgarten offers a toothy grin when I read the quotes back, and insists he’s not nearly as fist-clenchingly angry about the state of UK theatre as he sounds. OK, only slightly fist-clenchingly angry. “I love winding people up,” he says, raising his hands in the air in a gesture of mock defence. “But I stick by the idea that a lot of people go to the theatre to have their values reaffirmed. I want to do the opposite.”

No one could accuse him of not putting in the effort. Since he burst on to the scene in 2010 with an astringently funny satire on the BNP, A Day at the Racists, Lustgarten has unleashed a rapid fusillade of plays tackling everything from the banking crisis (If You Don’t Let Us Dream, We Won’t Let You Sleep) to the migrant crisis (Lampedusa) and the state of Zimbabwe (Black Jesus). His eye for reportage, and human-size stories that illuminate the bigger picture, is especially keen: Shrapnel, which opened in 2015, retold the story of a massacre of Kurds by US-assisted Turkish forces in 2011; The Sugar-Coated Bullets of the Bourgeoisie, which followed at London’s Arcola last April, focused on the long shadow thrown by the Chinese cultural revolution on one village.

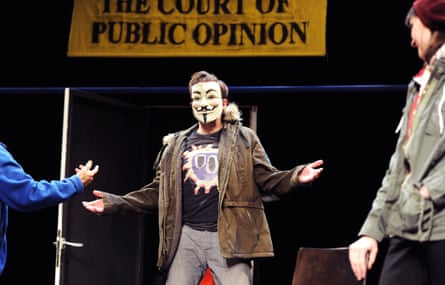

In a British playwriting scene that can seem nervous about tackling big ideas head-on, particularly when they concern complex global politics, Lustgarten – who began his theatrical life directing plays in prisons, and remains committed as a political activist – appears to have no such compunctions. Some have complained that the results are too pitchfork-waving and agitprop-y by far; one reviewer wrote that Lampedusa felt like being “heckled rather than stimulated”. The rebuttal might be that, in the age of Brexit and Trump, agitprop is exactly what we need.

Given all this, Lustgarten’s new script sounds surprising. Commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company, The Seven Acts of Mercy focuses on the canvas of that name by the baroque master Caravaggio. The painting itself is a depiction of Christian charity in action and is, characteristically, both brilliant and brilliantly unsettling: as angels wheel and soar above the frame, a mother suckles a starving man from her own breast while a corpse is carted away to burial, only its feet visible.

But anyone expecting the play to be a thesis on early 17th-century brushwork should brace themselves. This Caravaggio, played in the new production by Patrick O’Kane, is a swearing, swaggering loudmouth whose talent with a paintbrush is rivalled only by his dexterity with a hidden dagger. The daredevil image is, of course, historically accurate: directly before painting The Seven Acts, the artist had been forced to flee Rome after killing a man in a brawl, and the brazen sexuality of some of his pictures has led many to speculate that he might have been gay in a period when to be so was dangerous, to put it mildly.

Lustgarten’s own obsession with Caravaggio began when he visited Malta on an athletics trip; in another surprising twist to his CV, the playwright was once Scottish 400m champion at senior level and considered becoming a professional runner. He found himself standing in front of another powerful Caravaggio, The Beheading of St John the Baptist (1608) in St John’s Co-Cathedral, Valletta. “One of the other lads said he was going to see the painting on his day off. I ended up staring at this thing for two hours. Caravaggio is so sophisticated, so formally experimental, but his paintings are just visceral. He bangs you in the gut.”

Echoing Lampedusa, which entwined monologues from a Leeds debt collector and a Sicilian man who fishes bodies of refugees out of the Mediterranean, The Seven Acts transcends time as well as geography. It braids together the story of the painting’s creation with a parallel narrative set in contemporary Merseyside, where council flats are circled by sharkish developers and food banks are on the rise. Modern-day Britain, the play starkly suggests, is every bit in need of charity as 17th-century Italy.

The script also nags at a big question that Lustgarten, as an avowed leftwinger, admits is his too: whether art needs to be hitched to a social purpose. While Caravaggio blithely assumes that his paintings are so powerful that they are innately life-changing, this drama makes it clear that life is substantially more complicated, particularly if you happen to be bankrolled by the Catholic church. In Lustgarten’s view, “the whole play is taking on Caravaggio’s idea that he fights for the people and makes things better through his work. It’s a nice romantic vision, but it’s bullshit, I think.”

Is there a hint of his own in-out position, as a man who has repeatedly proclaimed his disdain for the British theatrical establishment, yet who now writes for some of the biggest theatrical establishments in the UK? He raises his hands defensively again. “I do know how lucky I am. Every time I get a play on, I feel lucky. But it’s good for me to do stuff in weird places like the RSC, because it challenges my own preconceptions and prejudices, of which I have as many as anybody else.”

Lustgarten certainly isn’t short of opinions: moments after declaring that “most playwrights write to win awards, and there’s something morally corrupt about that”, he concedes that he has won the odd award. Minutes later, our discussion is almost derailed by a 20-minute disquisition on Corbynism and the shortcomings of the liberal media – the Guardian and BBC included. The only moment he seems genuinely tongue-tied is when I ask him what he does for fun; marathon training and drum’n’bass clubs, he eventually admits.

It’s hard not to warm to him, particularly for his blazing-eyed belief that theatre, if it wants to matter to wider society, has to do its utmost to change that society. “In theatre, you can entertain, and you can also say something about the world. There’s not another medium like it. You can’t fake it, you can’t commodify it.” It has even more of a duty to do so given the current political situation, he adds, citing one playwright he does admire, Arthur Miller. “It’s our duty to stand up. If someone stands up, then other people jump in behind.”

He’s as busy as ever. In between commuting to Stratford-upon-Avon for rehearsals, he’s recently completed a short piece on the housing crisis for the Cardboard Citizens troupe, which works with performers who have been homeless or otherwise socially marginalised. He’s mulling a piece on the legacy of the British empire. And he’s just returned from a two-week trip to Israel and Palestine, researching for yet another new project, this time for the National Theatre. He describes it as “trying to see the world from a Zionist perspective”.

Nicely uncontroversial, then? He grins again, and flexes his knuckles. “Oh yeah, it’s not going to wind anybody up – no one at all.”

- The Seven Acts of Mercy is at the Swan theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, 24 November–10 February. Box office: 01789 403493.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion